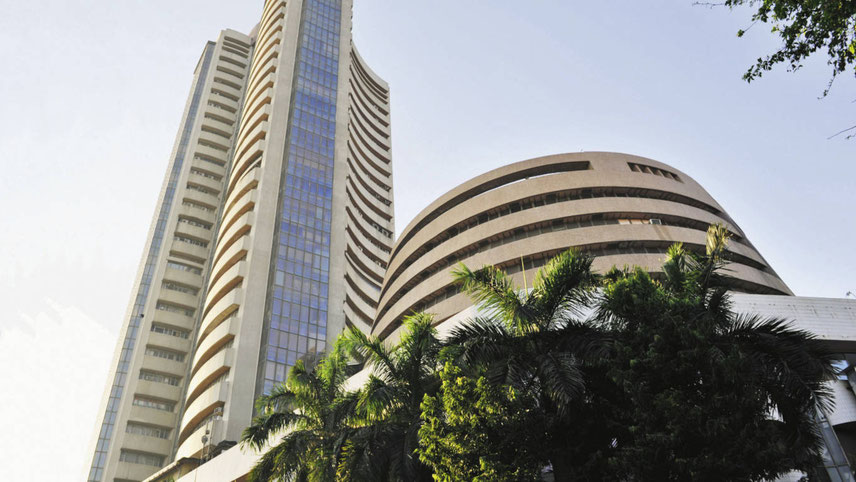

When, on 22 January evening, the farmer leaders left Vigyan Bhawan in Delhi after the 11th round of failed negotiations in the last 58 days with Narendra Tomar, minister for agriculture & commerce, some of them had a new grudge to add to their long list of grievances against the Union government – of a volte face. After showing little flexibility during the rounds before that, there were indications from the government quarters in the ninth and 10th rounds that it may agree to suspend the farm laws (earlier hailed as Indian agriculture’s 1991 moment, before assuming a contentious character especially for farmers of two states – Punjab and Haryana) for more than a year. The suspension period was supposed to be utilised to thrash out differences through further discussions and negotiations with the expert committee appointed by the Supreme Court playing a pivotal role. (The three farm bills have already been put on hold by the apex court.) But with the committee of farmer leaders representing over 40 unions refusing to budge the agriculture minister had reportedly walked out, saying the government can’t go beyond this. Later, in his briefing to the reporters covering the event, Tomar specified that the government would still wait for the farmer unions to show flexibility, while adding that there seemed to be forces with ulterior motives in the play, hell-bent on keeping the two negotiating sides away from the middle ground of détente. The farmers’ agitation being witnessed in the key northern states (traditional agricultural powerhouses), with the main stage shifting to the national capital subsequently, is an unfortunate development – especially at a time when the country is fighting hard to come out from the unprecedented devastation inflicted by the Covid-19 pandemic. And undoubtedly, the Union government can’t easily exonerate itself from its share of blame for having allowed the situation to reach this far. A popular theory doing the rounds in Delhi circles is that the Modi-Shah duo has little understanding of the basic DNA of the working population of these two states, where linkage with agriculture and allied sectors is intrinsic, running for several generations. Dissuading them from their occupational belief system and practices would be easier said than done. There is no denying the fact that the country depends on the farmers of these two states for self-sufficiency status in food grains. Their hard efforts since the 1960s have contributed immensely in bringing the country to a stage where it has become a leading global producer across several commodities in the staples. However, before we surrender all our reasoning at the altar of annadata belief or rhetoric, there indeed is a strong case of persuading them to modify the driving practices of their occupation.

-

Illustration: Panju Ganguli