-

The planet will close the year with an average 1.4°C warming above pre-industrial levels

Like its predecessors, this industrial revolution will necessitate changes in the means and mode of production and it will affect nearly every sector – energy, industry, agriculture, transport, buildings, mining and deforestation to name the big ones. Early participation in the energy transition will set the foundation for the green transition, but this is only the beginning.

Further, like its predecessors, this industrial revolution will lead to the largest transfer of wealth in history. This could be good, creating a more inclusive economy or it can further exacerbate economic disparities. How closely India marries its economic development to the green transition will have as much, if not more impact on socio-economic development as initiatives targeting a just transition.

The Making of the Green Industrial Revolution

Industrial revolutions are borne of rapid adoption of new innovations that fundamentally transform economic development, often paired with new financial instruments to enable rapid dispersion. In this case, the drive for new technologies is in response to the scope and scale of changes required to keep climate change within liveable temperature bands.

This will require nothing short of replacing the vast majority of chemicals, materials and processes used in the production of goods, food and services associated with a developed middle-class lifestyle. How homes and roads are built must change, as must how factories operate.

For India, the fastest growing major economy, this is especially true. By 2030, manufacturing and energy requirements are projected to double, while consumer spending is expected to reach $6 trillion a year – a full 1.5x the current national GDP.

To achieve the promise of India’s economic development will require that new and existing manufacturing decarbonise early, accelerated adoption of innovations with a viable value proposition and dramatically improved capital efficiency.

If India follows China’s emissions trajectory as it develops, it will use 70 per cent of the global carbon budget. This means that even if the US, Europe, Russia, China, the Middle East, and other developed nations ALL meet net-zero objectives by 2040, the planet would not be able to stay below 2° C. None of these economies are on target to reach net-zero within this time frame.

Silver Linings

Leaders in Indian industry (like Mahindra, Tata, Dalmia, Jindal to name only a few) have been early adopters of decarbonising technologies like heat pumps and new materials, with Indian cement having the lowest average carbon footprint amongst major economies. Similarly, corporates working with start-ups benefit from better access to technology, faster development time and can offer higher return on investment.

-

Early transition is already reaping economic benefits for these companies through immediate cost benefits, shareholder pricing and competitiveness in international markets.

Drawing lessons from these industrial leaders to green SMEs and industrial production is one step in India keeping its per capita carbon usage in check. Another is to develop pathways for rapid adoption of innovations with cost effective emission reductions.

To accelerate the adoption of such innovations – technologies or processes – often requires mechanisms to achieve techno-commercial validation, aligning business models and capital structures to the reality of the market, and access to appropriate capital.

To be viable, climate innovations must be price and quality competitive. To build climate viable businesses we cannot fight human nature. Price, aspiration, and convenience are the drivers of consumer decision-making. As climate change has become mainstream and climate-friendly products have become aspirational, market forces have shown consumers will make luxury, identity and low-cost impulse purchases despite price. In the vast majority of instances, however, climate-friendly goods must be better, cheaper and/or significantly more convenient than the status quo to achieve adoption.

This is one of the areas in which India’s innovators truly shine

It is only when climate innovations are price and quality viable that funds will flow freely, but more capital or higher capital efficiency will be necessary to achieve climate and economic development goals.

-

Indian cement industry has the lowest average carbon footprint amongst major economies

Niti Aayog estimates that India needs $160 billion dedicated climate investment per year through 2070 to achieve its net-zero goals. This does not include economic development, investment or social inclusion requirements. This quantum of capital is not available at present.

Industrial revolutions often require adaptations in the financial markets to achieve rapid adoption and scaling of technology availability. A few financial adaptations that would support the transition include:

• Incorporation of climate risk in loan underwriting to equalise or benefit green financing terms – interest rates should not be dramatically cheaper for new dirty technologies when proven green technologies exist.

• Availability and reliance on equity to adequately reduce technology and business risk to create appropriate pipelines for lenders. Equity is intended to be higher risk capital than loans. In properly functioning markets, equity is intended to de-risk companies. When loans are de-risked, interest rates and NPAs should both reduce.

• Results-based financing can be leveraged to help agrarian communities transition and participate in the economic benefit of the green economy. Registration and certification costs are prohibitive for low-income participants most in need of the economic benefits carbon markets offer. India’s farmers are responsible for food security. More than any other group, agrarians will bear the brunt of climate change and need support in the transition.

• Regulations that carbon and similar credits only be used to offset emissions that cannot yet otherwise be mitigated.

Climate change impacts will not be limited to extreme weather, health, and price increases. It impacts larger economic markets through supply chain disruptions and shifting commodities prices. We have only seen the early impacts of climate change. Baked-in emissions and transition timelines assure that impacts will become more intense and extreme.

Innovation across industry, policy, and finance will all be required to meet the risks and opportunities of the climate challenge.

Embracing systemic and coordinated changes based on market viability will be necessary. Silver bullets may be part of the solution but building on its many silver linings will be India’s true strength.

-

If India follows China’s emissions trajectory as it develops, it will use 70 per cent of the global carbon budget

|

Reality check

|

|

Intervention

|

|

|

Hydrogen

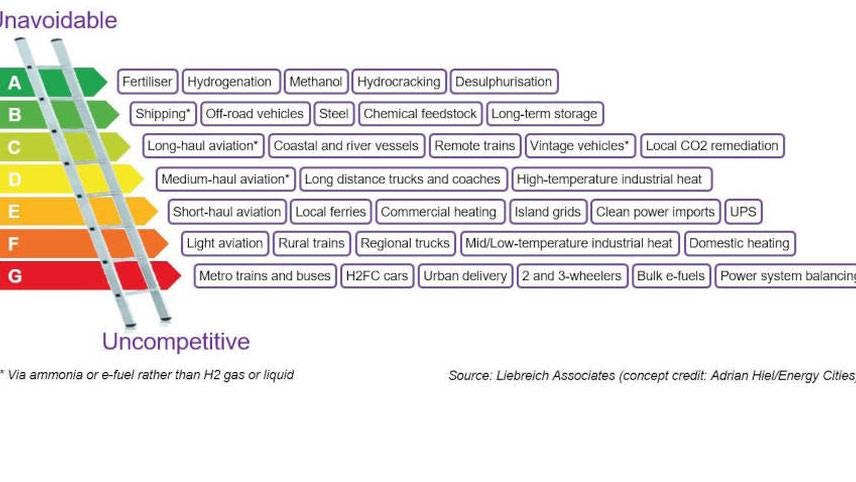

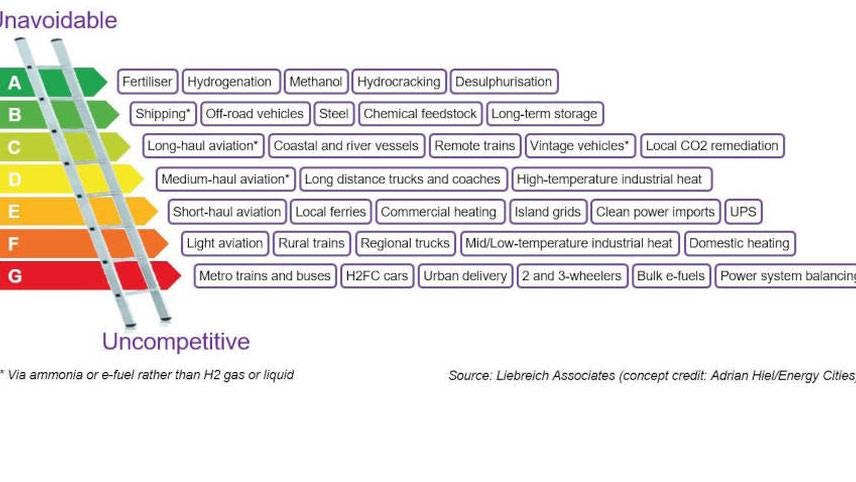

Hydrogen is being touted as a super fuel alternative to replace coal, gas and oil across myriad use cases. Green Hydrogen, the cleanest form is produced through electrolysis to split water into oxygen and H2 atoms. Touted as a clean and low-cost replacement for everything from transport and boilers to fertilisers, hydrogen has many drawbacks.

|

• Requires an average of 9 litres of water to produce 1 litre of hydrogen

• Energy inefficient with 30-40 per cent loss of energy in production and another 30 per cent energy loss in the storage process

• It is not a drop-in solution for existing industrial processes. Boilers will require costly retrofits to transition.

• Existing gas pipelines are not viable for hydrogen gas. Its smaller molecule size will lead to higher leakage

• Transport costs are 2-3x product cost due to low density (requires lots of space) and temperatures requirements (-253° C)

|

|

Micro- Nuclear/Small Modular Reactors

Small modular reactors are being developed with the intent to modularise and industrialise production of reactors for rapid deployment, particularly in remote or disaster-hit areas or to sit on the footprint of decommissioned coal plants to provide baseload zero-carbon energy. Due to safety and security risks long technology development and approval cycles have prevented commercialisation.

|

• To date many reactor designs are still reliant on HALEU fuel (enriched uranium), leading to risks of proliferation. Newer models using thorium are safer but still produce an isotope that can be irradiated into uranium for weapons purposes

• Several studies indicate the capital cost of SMRs to be equivalent to larger reactors. Security and insurance costs are similarly expected to be on par with traditional nuclear, while power production is lower

• A Stanford study indicated that radioactive waste from SMRs will be higher than conventional nuclear reactors

• Fuels are not widely available

|

|

Fusion

In 2023, scientists were able to demonstrate positive energy production from nuclear fusion, touted as the holy grail of free, clean energy. Mimicking the energy production of the sun, fission occurs when two atoms slam together to form a heavier atom, like when two hydrogen atoms fuse to form one helium atom. The energy production of such a reaction is several times greater than traditional nuclear energy without radio-active by-products and only small amounts of helium. While it is yet to be demonstrated at any scale, 1 kg of fusion fuel could provide the same amount of energy as 10 million kilograms of fossil fuel.

|

• Still limited ability to repeat positive power generation

• Requires extreme temperatures (150 to 200 million degrees) and energy to produce

• Some scientists suggest Deuterium and tritium reactivity makes fusion possible on earth but releases excessive neutrons that function similarly to radioactive waste

• Tritium, one of the most commonly used molecules in testing is rare and requires extreme cooling demands and operating costs to maintain.

|