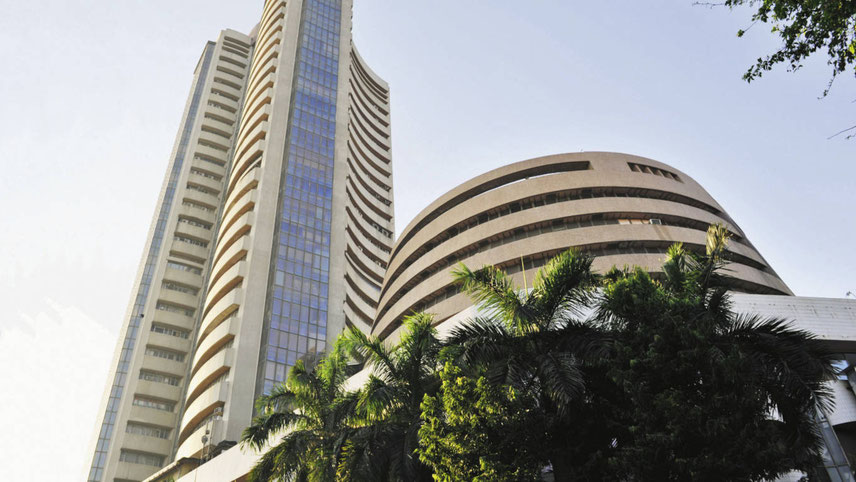

The outpouring of sheer joy among the denizens of Mumbai at the resumptions of local trains on 1 February is testimony to the vital role that suburban trains have played in people’s lives. Ever since the movement of local trains was suspended in Mumbai about 11 months ago, the city has struggled hard to maintain some level of normalcy. But it has mostly been an unequal battle, with offices across the city remaining closed, small businesses closed or operating at a subsistence level and hundreds of thousands of people confined to their homes. All this changed dramatically at the beginning of the last fortnight when the government agreed to allow ordinary people to travel in the local trains. In the first week after the government decision, more than three million people boarded the local trains, in the two arterial services operated by the Central and Western Railway zones. The photograph of a young man bowing at the entrance of a local train created a social media storm. Even Anand Mahindra, the leading industrialist, forwarded it on Twitter. It was the most poignant expression of emotions that the local train evokes in Mumbaikars. Another photo showed a delighted commuter displaying a placard that said: “I have forgotten Dadar kaunsi side aata hai!” That’s the impact of 11 months of life without local trains. In fact, the easing of restrictions began in June 2020, when the local train services started operating in a limited fashion. This was done to enable those working in essential services – hospital employees, police officers, those involved in banking, utilities (water supply, electricity, etc) and even mobile companies were allowed to travel. Even then, everyone boarding a train had to carry ID cards or other proof that they were genuinely employed in the recognized categories. But the railway services were few and far between, making it difficult for users to maintain duty timings. Hence a majority of such employees had to fend for themselves, sharing cabs with colleagues after paying exorbitant amounts, or commuting by private buses. However a city like Mumbai could not run indefinitely on essential services alone. Shops and small businesses could not be supplied; everyone waited for better days to come. “We are unable to replenish our stocks, but any customer that we turn away might never come back,” said a chemist shop owner in Mumbai’s suburbs. Therefore, as the Covid-19 situation changed for the better all over the country, people began to get restive, wanting to know why the government was not lifting the restrictions. While no one would go on record, railway officials admitted in private conversations that their systems and processes were fully prepared to run the local services by the end of December.

-

Illustration: Panju Ganguli