-

Vaishnaw: cargo movement is faster now

Gathering speed

Trains have achieved an average speed of 50-60 km per hour (and can be increased up to 100 km per hour) on these dedicated tracks, at least thrice the speed of goods trains that run on regular tracks of Indian Railways where average speed is in the 20-25 km per hour range.

“The time needed to reach from one place to another has now reduced by 50-70 per cent after the introduction of the freight corridors,” claims Ashwini Vaishnaw, Railway Minister. “After the cargo trains have been shifted to the freight corridors, passenger trains have stuck to their conventional routes. This has given more capacity to passenger trains.”

The DFC project will also help in ‘predictive maintenance’ in which trains can be repaired and maintained before they are about to fail which will, in turn, increase the efficiency of the system, he adds.

Yet, now, doubts are arising over the viability of the DFC. The Modi government, unable to hard sell the two projects to users, believes that the capacity utilisation of the two corridors is still low – and any expansion to be undertaken for augmenting the freight movement will have to be more targeted or commodity-specific. It’s back to the drawing board for the Dedicated Freight Corridor Corporation of India Ltd (DFCCIL), the nodal agency for the project.

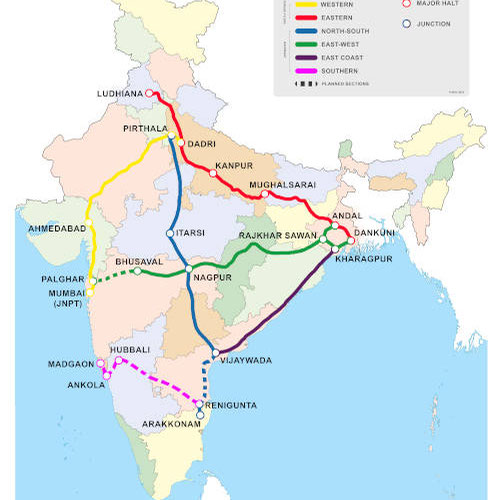

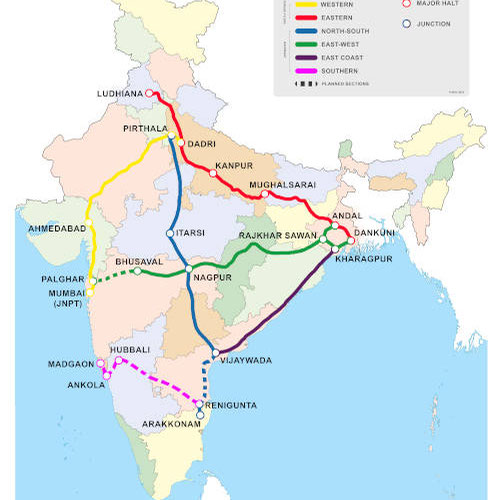

Western Corridor

As things stand today, the Western Dedicated Freight Corridor (WDFC) covers 1,506 km and connects the JNPT port (in Mumbai) to Dadri in Uttar Pradesh. The states covered include Maharashtra, Gujarat, Rajasthan, Haryana and UP. The operational routes cover 938 km of Dadri-Sanand, 244 km of Makarpura-Gholvad, and 77 km of Gholvad-Vaitarna. The 138 km stretch of Sanand-Makarpur is about to be operational.

Work is pending along the 110 km odd route between Vaitarna and JNPT port due to weather conditions, the subsequent reduction in the work period, and trouble with the contractor. The completion of work along this route is expected in the next one year after which the entire stretch of the WDFC will be operational. At present, 100 trains are running along the WDFC.

Eastern Corridor

On the other hand, the entire 1,337 km Eastern Dedicated Freight Corridor (EDFC) is operational. The route covers Sahnewal-Khurja, 401 km; Khurja-Bhaupur, 351 km; Bhaupur-DDU (Deen Dayal Upadhyay junction formerly called Mughalsarai), 402 km; DDU-Sonnagar, 137 km; and the Khurja-Dadri section, 46 km.

The network traverses Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand and Bihar, through which 200 trains run daily. A 538-km route between Sonnagar and West Bengal, originally proposed to be part of the EDFC but subsequently removed from the project, will now be developed directly by the Ministry of Railways.

Curious turn

However, here’s where the things get curiouser. At least three more dedicated freight corridors, including commodity-specific routes, were being considered as part of the Indian Railways’ plan to push faster freight movement and free up regular tracks for passenger trains. Covering the east coast route, the north-south trail and an east-west one, the three corridors were to cover a total length of 4,300 km, with the estimated project cost being Rs2 lakh crore.

-

Dedicated Freight Corridors of India

However, suddenly there is now a rethink on the need to develop these corridors on traditional lines. In her interim budget speech, Nirmala Sitharaman, finance minister, announced exclusive corridor projects for specific commodities – energy, mineral and cement – and for specific purposes like port connectivity, and high-traffic density. “The projects have been identified under the PM Gati Shakti for enabling multi-modal connectivity. Together with DFCs, these three economic corridor programmes will accelerate our GDP growth and reduce logistic costs,” she said recently.

The announcement in the Budget was seen as a deviation by the Modi government’s previous plan in this regard. In her Budget 2021-22 speech, Sitharaman had announced the launch of the generic East Coast, East-West and North-South corridors. A lot of spadework had been done.

Three network alignment reports were being prepared by the DFCCI. While two of the DPR have been submitted, a third will be ready by April-end. The government was also prioritising decongesting the Delhi-Howrah and Delhi-Mumbai routes to ensure faster movement of freighters and free up tracks for improved running of passenger trains.

East Coast track

According to officials in the know of things, the first dedicated freight corridor so proposed is along the East Coast running almost parallel to the existing coastal passenger rail line and covers an approximate distance of 1,200 km starting at Kharagpur (West Bengal) and terminating in Tenali (in Andhra Pradesh).

The initial plan was to end the route at Vizag, connecting the port, but was subsequently increased to Tenali. This route passes through the mineral bearing states Bengal and Odisha, connecting the Vizag port too. The target sector includes coal, fertiliser and iron-ore movement apart from other commodities like steel.

North-South corridor

The second route or the North-South Corridor covers Itarshi (in Madhya Pradesh) to Tenali, a distance of 1,000-1,200-odd km. The proposed corridor will pass through Itarsi-Nagpur-Vijayawada and end at Tenali. It will pass through four states that include Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh. Traffic would cover coal, cement, fertilisers and petroleum & oil lubricants, among others.

The long-term plan is be to connect Dadri in Uttar Pradesh with Itarshi. This will allow connecting the existing and operational Dedicated Freight Corridor with the upcoming one.

Third corridor

The third corridor, which is still under-preparation, covers the East-West route connecting Andal (West Bengal) with Palghar (Maharashtra). This route passes through five states which include West Bengal, Jharkhand, Odisha, Chhattisgarh and Maharashtra. The main line covers close to 2,100 km and there will be spur lines with additional 300 km.

The major traffic generators would be coal and iron-ore, bauxite, manganese, ferro alloys, steel, ports – major and minor – fertilisers, thermal power plants, PoL cement plants, Container Corporation (CONCOR), Inland Container Deports (ICDs), Food Corporation of India (FCI) godowns, among others. A final call on funding, alignment and how to carry out these projects was in the works.

So, why is the government abandoning the plan to set up three more DFCs – East Coast, East-West and North-South – at an estimated combined cost of Rs2 lakh crore and opting for commodity-specific rail networks.

The move, according to sources, comes in the wake of the railways having to hard-sell the recently commissioned east and west freight corridors to potential bulk customers, and the issues that have cropped up of the network planning of these projects. The capacity utilisation of the two corridors remains low.

-

The new corridors should have a multi-operator regime and a beginning should be made with the DFC

Many retired officials of the Railways Ministry feel the rethink on the character of three additional DFCs should have come earlier and not after the Railway Board received the detailed project reports for two of them (East Coast and North-South).

The Railways, however, believes that, despite occasional surges, the average capacity utilisation levels of the 1,337-km EDFC and 1,506-km WDFC remains fairly low. EDFC connects power plants in the northern states of UP, Delhi, Haryana, Punjab and parts of Rajasthan with Eastern Coal Fields. Traffic on EDFC also comprises finished steel, food grains, cement, fertilisers and limestone. WDFC, which still has a 109-km stretch under construction, is being used primarily for export-import container traffic and transporting milk from Gujarat to northern India.

Fait accompli

But now that the decision has been taken, the Railway Board and the DFCCL have already met once to push the idea. If implemented, the previous three proposed corridors would have a combined length of 4,315 km. As per DPR, the 1,078-km East Coast corridor will connect Kharagpur to Vijayawada, and 931-km North-South corridor will connect Itarasi to Vijayawada.

The third East-West corridor is divided into two sub-corridors: 2,106-km Palghar to Dankuni section and 200-km Rajkharswan to Andal section. The proposed corridors aimed to slash the transit time of freight trains, bring down the overall logistics costs, and further enhance the railways’ share in the total cargo movement.

Bigger customer base but…

The new thinking is that commodity-specific corridors is predicated on the premise that there will be existing customers for them. A Railway Board study, for instance, underscores the need for having dedicated coal freight corridors to meet the escalating power demand in India. These corridors would pass through Jharkhand, Odisha and Chhattisgarh where the bulk of coal transportation originates to the north, west and southeast of the nation.

But is the plan realistic? Coal India Ltd (CIL) is likely to be the largest contributor to new coal production and has the most ambitious goals – floating plans to move an additional 400 million tonnes by rail in just four years. As per the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, This timeline appears unrealistic, especially since almost all the extra 91 million tonnes that CIL has mined in the last two years moved not by rail but by truck. The company now reports more than 600,000 truck movements each month. Meeting CIL’s targets requires a rapid reversal of this trend.

The ministry for statistics & programme implementation has warned that railway projects are the second-most delayed category of infrastructure, so timely completion is not guaranteed. Railway planning also issues guidelines that appear to exclude the possibility of negative ‘network effects’, resulting from new coal traffic worsening congestion outside the immediate project area.

Same challenges

Experts believe that the new commodity-specific corridors are expected to face the same set of challenges which the DFC faced. Land acquisition was one of the biggest hurdles in DFC. About 11,000 hectares of land in nine states spanning 77 districts was acquired for the DFC. Another challenge was shifting of utilities. Contract management and obtaining of regulatory clearances were other challenges.

-

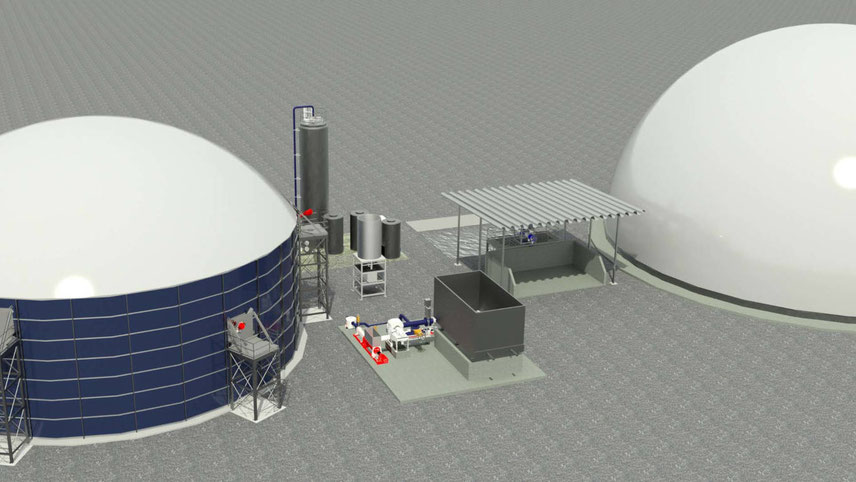

Western Corridor: connecting the JNPT port (in Mumbai) to Dadri in Uttar Pradesh

The government will also have resolve issues like freight tariff. Manish Puri, an independent consultant & president, Association of Container Train Operators, points out that although, traditionally, the railways’ rate per-tonne km has been cheaper, rail is not an end-to-end service like road. “For instance, in containers and other similar cargo, where penetration of the railways is 5 per cent, current per-tonne cost of cargo on road, end to end, is cheaper than on the railways,” he said.

The new corridors should have a multi-operator regime and a beginning should be made with the DFC. Right now, no private operators run trains on the DFC. It’s a single-operator regime. In theory, the government has agreed to a multi-operator regime but to practise it the government has to make the project self-sustaining.

There have been notable recommendations from several committees in the past, including the Rakesh Mohan Committee, Sam Pitroda Committee, and Bibek Debroy Committee, to delink the regulatory role by establishing an attached office or statutory body. Although the country announced the formation of a Rail Tariff Authority in 2014 and a Rail Development Authority in 2017, these entities are yet to be formally set up.

This clearly is an agenda that the new government will have to take up in right earnest.