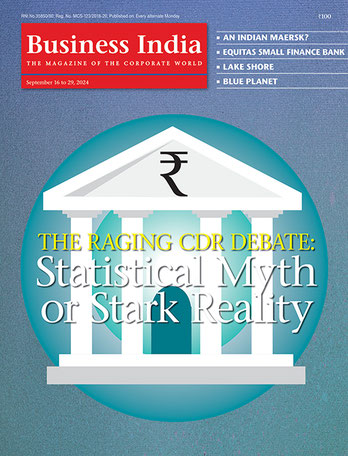

In the dark comedy ‘Serious Men’, on Netflix, the principal proponent Nawazuddin Siddiqui explains the concept of 4G in business thus: “The first generation emerges and is uneducated; he educates the second generation through school but the second generation barely scrapes through; the third generation receives proper education and he is the fighter to change his family fortunes and the fourth generation relaxes and enjoys the fruits of hard work of the previous generation.”It’s the same in the business world of today. India is passing from the third generation to the fourth generation. Since time immemorial, Indians have been known throughout the world for their entrepreneurial pursuits. Wherever any Indian set shore, they set up their small enterprise. Be it the corner shops in the UK, the Patel Motels in the US or the retail business in East Africa, the entrepreneurial spirit of the Indians has always been admired globally. The same pattern held sway within the country as well. India was a land of entrepreneurs and the average Indian would start their small businesses and then would slowly grow the same. The businesses were varied – from running small shops, to being stockists of large companies, to becoming vendors to the government, to start-ups, to SME businesses in manufacturing – but this was the growth driver of the country in the early years, post-independence too. And entrepreneurs always needed money to grow their business. India didn’t have access to private capital; and, so, the main funding source for small enterprises used to be bank funding, while the larger enterprises used the capital markets. That was, in essence, the Indian business DNA for decades till 2010. But, during the last decade, a remarkably interesting phenomenonhas appeared in the Indian psyche and the business world. Let us take the life of an average successful entrepreneur in India’s Tier II/Tier III cities. The entrepreneurs of the hinterland worked hard to be suppliers to the government or ran their small manufacturing businesses. They built their business brick by brick. They rarely understood the value of equity and were driven by cash flows. Given the backdrop of the ‘sarkaari interference’, they would cosy up to the local government machinery, would keep two account books and would work hard to pay as little tax as possible. While they lived in personal comfort, they rarely ensured growth of their business and would mostly starve their businesses out of cash flows. But they had strong aspirations for their children. They worked hard and send the next generation overseas – to the US, the UK, Canada or Australia – for their higher education. Once these children came from abroad with their new-fangled knowledge in business, they would try their newer ideas to make changes in their generational business. But alas, in most cases, they couldn’t make any changes. The factory manager of his father’s business may have been there for 30 years and had loyalty running in his veins, but he would loathe any change. The main accountant was the family munim, who knew what to show in the business and what not to, knew all books of accounts and knew the entire history. The patriarch trusted him more than his children. In most cases, these new 4G foreign returned business experts could make no difference in the business and this frustrated them and they became disinterested in their family businesses.