The moral responsibility of boards

It seems boardroom ethics confines itself to glossy annual reports, governance seminars and legal memos and is not really interrogated with the seriousness it deserves. Boards are fluent in the language of compliance but far less comfortable in the language of conscience.

Business schools, law firms and governance consultants have done an admirable job of mapping the outer boundaries of misconduct. Directors are coached on the dangers of fraud, insider trading, conflicts of interest, breaches of confidentiality and self-dealing. They are reminded that personal liability, regulatory wrath, and reputational ruin await those who stray beyond legal limits.

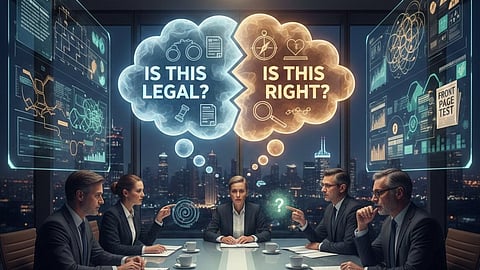

This legalistic clarity is necessary and valuable. A director who does not understand their compliance obligations is not merely negligent – they are a risk to the enterprise itself. This framework suffers from a profound limitation: legality is not morality. The question: ‘Can we do this without breaking the law?’ is not the same as ‘Should we do this?’ A board that treats legality as its ethical North Star risks becoming technically clean but morally hollow.

The true ethical burden of a director extends well beyond what company counsel says the firm can ‘get away with’. At the heart of board responsibility lies two foundational fiduciary duties: the duty of loyalty and the duty of care. On paper, these appear distinct – loyalty demands that directors act in the best interests of the company and its shareholders, free from personal gain.

In practice, however, these duties converge into something more intangible but far more powerful: the ‘tone at the top’. This is not a slogan – it is the cultural gravity field of the organisation. The board does not merely supervise ethics; it embodies them. Employees do not learn integrity from policy manuals; they learn it by watching how directors behave when decisions are difficult, ambiguous, or inconvenient.

Consider a seemingly routine procurement decision. The board is evaluating a major vendor contract. If a director openly steers the company toward a firm in which they hold a direct stake, the conflict is obvious and likely disqualifying. But ethical challenges rarely arrive in such stark form. What if the preferred vendor once extended a personal favour to a director? What if the director’s son-in-law recently joined the vendor’s sales team? No law may be broken, no formal conflict declared – yet the board’s moral posture is already compromised.

These are the grey zones where real governance character is tested. Ethics here is not about avoiding prosecution; it is about avoiding moral erosion. A board that normalises subtle self-interest teaches the organisation that integrity is optional so long as it is well-disguised.

The tension between loyalty and care becomes even sharper when warning signs of wrongdoing emerge. Suppose management presents financial data that vaguely suggests possible internal fraud, self-dealing or bribery. If the evidence is clear, the board must act decisively. But what if the signals are faint, ambiguous or buried beneath mountains of dense reports that no human could reasonably parse in a board meeting?

This is not a hypothetical problem. High-profile failures – such as the Australian Star Entertainment case – illustrate how boards can be inundated with information yet remain functionally blind. Data overload can become a convenient excuse for inaction. Ethical directors, however, do not hide behind complexity; they challenge it. They ask uncomfortable questions. They demand clarity. Most directors refuse to question well-presented narratives.

Real boardroom ethics is not a holy scripture you mumble before lunch – it’s more like street-smart yoga for suits: stretch the conscience, not just the clauses. Directors can chant ‘no bribes, no bias, no drama, follow the law’ all day, but real leadership is about vibes – how things smell to regulators, workers and the relentless court of Twitter. Slick tax tricks, green-washed sparkle and sweatshop couture may pass legal muster, but they scream that decency is a mood, not a mandate. The boldest boards don’t just read what’s served; they sniff out what’s been swept under the carpet and hunt the secrets management hoped no one would notice.

In a world where everyone is watching – activists, investors, journalists and keyboard vigilantes – boards can’t hide behind legal jargon anymore. Their credibility now depends less on paperwork and more on backbone: being profit guardians with a moral spine, not just polished rule-followers in expensive chairs.

Ultimately, the most powerful question a board can ask is not ‘Is this legal?’ but ‘Would we be proud to defend this decision on the front page of tomorrow’s newspaper?’ That question – uncomfortable, demanding and profoundly human – is the true compass of boardroom ethics.