-

Beneficiaries of a women empowerment project in Murshidabad District, West Bengal

tudying the current events in corporate India, it can be said that over the last few centuries, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in the Indian context has come a full circle. As historians have reported, in ancient times, merchants and their guilds (Mahajans), while focusing on the development of their trade, collectively worked for and contributed to the welfare of the entire village or town. In a way, the responsibility of citizens’ welfare was of the Mahajan, the funds for which were contributed by affluent traders of the day. In times of famine, epidemic outbreaks or other natural disasters, they promptly supplied funds and food for the needy. They also dedicated wells, tanks and temples for public use, provided rest houses for pilgrims and night shelters for wayfarers. They provided drinking water and sanitation facilities, built bathing ghats and animal welfare centres, and planted trees by the roadsides. They made liberal donations for education and healthcare, and met the marriage expenses of underprivileged girls. On special occasions and festivals they also arranged for the distribution of food. Such was the feeling of camaraderie in the Mahajan that Muslim traders belonging to a Mahajan contributed for the upkeep of Hindu and Jain temples and vice-versa. All these acts of benevolence also had the effect of raising their social status, gaining public acceptance, and political and trade influence. The Marwadis, Parsis, Gujaratis and Chettiars are among the legendary merchant groups noted for their very generous charitable contributions. CSR: pre-Independence to post-liberalisation A visionary quote of Jamsetji Tata, founder of the Tata group, continues to guide the conglomerate even after a century. He had said: “In a free enterprise, the community is not just another stakeholder in business, but is in fact the very purpose of its existence.” Noble philanthropists like him, belonging to the pre-independence era, contributed their might towards social progress and nation building. The prominent names being N.M. Wadia, Lalbhai Dalpatbhai, Baldeodas Birla, Jamnalal Bajaj, Lala Shriram, Ambalal Sarabhai, T.V. Sundaram Iyengar, among many others. However, post-independence, the enormous emphasis of the government of India on following a socialist approach of creating equity in society – through extremely high levels of taxation – had a negative impact on philanthropy. During this period, personal rates of taxation went up from 77 per cent in 1960-61 to 97.75 per cent in 1972-73, when it became one of the highest in the world. There was no possibility of using surplus funds for social welfare activities, as there were none! For a long period, social welfare became the government’s sole responsibility. After a quarter century of a controlled and protectionist regime, in 1991 the government liberalised the economy to a large extent. With the rise in levels of corporate affluence, several leading and new age Indian multinationals played their role as responsible corporate citizens. The more liberal tax regime enabled business organisations to now earmark part of their annual profits for social and environmental purposes. This was true of most big companies that were industry leaders with huge market share and resources. By 2009, the government of India introduced the National Voluntary Guidelines where companies, especially in the public sector, were advised to contribute to CSR initiatives through a part of their annual profits. With the introduction of Indian Companies Act 2013, reporting of CSR spending was made mandatory for companies from the public and private sectors based on certain criteria. One of the key reasons for this could be that as a mixed economy, the interests of corporations and the common citizenry must be equally emphasised. While corporations received huge benefits post-liberalisation, the common man was far from self-sufficient. The CSR legislation acted as a reminder to successful companies to fulfil an important obligation towards the disadvantaged citizens of India. Thus, the approach of collective responsibility of the merchant guilds of taking care of the less fortunate people at the ‘bottom of the pyramid’ has, through various centuries, come back in the modern set up, albeit through regulation, in the form of collective responsibility of corporate India, complementing the efforts of the government and civil society organisations.

-

Students and staff of a CSR-supported primary school in Tiruvannamalai District, Tamil Nadu

The CSR Legislation: context

It was Bjorn Stigson, former president, World Business Council for Sustainable Development, who observed that “the Millennium Development Goals cannot be achieved without partnerships between governments, business, and civil society. Business will bring in the financial and management resources”. By their very constitution, companies have the scale of resources – financial, technological, intellectual and human, to make a positive difference to the lives of people.

Corporations attract the best of human capital from the country’s education system. More than the funds, it is the use of this knowledge and skills, and the virtues of efficiency and effectiveness that the private sector can bring to social welfare that far outweigh their economic contribution through CSR. (An annual Rs12,000 crore through CSR funds may not contribute substantially to the government’s development agenda, especially when the funds are divided over a dozen causes.)

While the government has the mandate to focus on social issues, it may not always have the necessary skill sets and intellectual capital to solve the complex problems India faces. There is evidence that a cement company can do a better job at running a school than the government, and a steel company a better job at running a hospital – even though it is not its business. CSR provides an opportunity for companies to engage top talent (through social volunteering or pro-bono consulting) to ideate ways to solve critical issues, as pilot projects. If successful, they could be replicated and scaled at national levels in partnership with government institutions.

Though effected during the UPA II government, the Modi government has increasingly created avenues for corporate participation through CSR in many of its critical missions including Swachh Bharat, Digital India, Skill India and the urban renewal mission (AMRUT). It is an opportune moment for India’s corporate leadership to consider a change in its approach to CSR – from charity, to a social investment in creating infrastructure, resolving resource crunch and sustaining natural capital. With proper assessment and selection of projects that are aligned with a corporation’s core competence, the initiatives are bound to be even economically rewarding in the long term.

The CSR Legislation: content

Section 135, Indian Companies Act mandates:

1. Every company having net worth of Rs500 crore or more, or turnover of Rs1,000 crore or more or a net profit of Rs5 crore or more during any of the three preceding financial years, shall constitute a CSR Committee of the Board consisting of three or more directors, out of which at least one director shall be an independent director.

2. The CSR Committee shall:

a. Formulate and recommend to the Board, a CSR Policy which shall indicate the activities to be undertaken by the company;

b. Recommend the amount of expenditure to be incurred on the activities; and

c. Monitor the CSR Policy of the company from time to time.

3. The Board of every such company shall:

a. after taking into account the recommendations made by the CSR Committee, approve the CSR Policy for the company and disclose contents of such Policy in its report and also place it on the

company’s Website; and

b. ensure that the activities included in CSR Policy of the company are undertaken by the company.

4. The Board of every such company shall ensure that the company spends, in every financial year, at least 2 per cent of the average net profits of the company made during the three immediately preceding financial years, in pursuance of its CSR Policy. The company shall give preference to the local area and areas around it where it operates, for spending the amount earmarked for CSR activities. If the company fails to spend such amount, the Board shall, in its report specify the reasons for not spending the amount.

A dozen years ago, when I published my first research paper on CSR in India, I had highlighted three key aspects required to give CSR the importance it deserves:

i. CSR implementation would improve if its management responsibility is shifted from a functional head to a board representative.

ii. There is a need for transparent communication of CSR activities and spending by corporations on corporate Websites/in annual reports.

A consistent monetary commitment to CSR is desirable.

iii. I was delighted to find a three-fold approach to CSR investment and its intra-organisational administration in the Companies Act, 2013 that resonated with my research findings. These three include:

Structural

Through the mandatory requirement of a CSR Committee at the board level, the Act ensured an apex body at the highest levels of the organisational hierarchy, viz the company board, whose sole objective would be to initiate and regularly monitor CSR activities and related financials. This would bring focus on CSR at the highest levels, especially when many companies dealt with CSR as a public relations or corporate communications activity.

One of the primary reasons why CSR was not getting the much-needed thrust in most organisations was that top leadership, in most cases, did not consider CSR as a priority, and those actively associated with CSR initiatives were not having the seniority and mandate to make policy-level decisions and influence fair allocation of money for CSR. In my doctoral research study, conducted across 125 Indian companies from 18 industries and 18 cities across India, over 54 per cent of respondents observed that CSR implementation in their businesses would improve if the responsibility is shifted from a functional head to a board representative. This finding corroborates with the structure mandated in the Act.

Communication

In a 2009 McKinsey study, it was observed that many businesses pursued CSR activities that could best be termed pet projects, as they reflected the personal interests of individual senior executives (or even their spouses). The formation of an organisation-wide CSR Policy (and its vetting by the Board CSR Committee) as recommended in the Companies Act considerably removed the arbitrariness with which CSR activities were selected. The mandatory communication of the CSR Policy through the annual report and website of each company would lead to greater awareness of CSR initiatives among diverse stakeholders, including shareholders, researchers, media and analysts.

Financial

Insisting on a fixed CSR allocation by every company within a specified financial bracket would encourage focused spending exclusively for society and the local community, and reduce arbitrariness. It would also lead to reporting exact financial details on CSR in annual/sustainability reports, and websites. This would facilitate evaluation of investment-impact outcomes of different corporations by analysts and researchers. For example, in a study at Harvard Business School on CSR in India, we mapped the largest investments made by corporations, and the long-term and grassroots impact that these would potentially have. In the process, we noticed that many corporations have used massive CSR funds to build hospitals and educational institutions where 10 per cent of the funds are benefitting the poor and the remaining 90 per cent cater to affluent patients and students. Does this truly amount to CSR in spirit? Questions such as these could emerge in the AGMs of the future.

-

Does this truly amount to CSR in spirit? Questions such as these could emerge in the AGMs of the future.

The global CSR continuum

CSR has very distinct connotations in different parts of the world. This has lot to do with the domestic socio-economic situation. In countries with insufficient government funding for health, education and water supply, CSR activities in these areas would be far more relevant and value-adding than activities purely focussed on reduction of carbon footprint to tackle global warming. India, select countries in Latin America and South Asia fall in this category. To highlight the contextual relevance, I provide a brief overview to CSR as practised in different continents:

Europe

In the Nordic countries, and select countries from the European Union, where there are well-established social security programmes for citizens, and lowest poverty levels in the world, companies lay greater emphasis on greening their supply chain, and producing and promoting environmentally responsible products. When I was a Visiting Scholar at the Copenhagen Business School, I observed that most Scandinavian and West European countries considered CSR to be synonymous with Sustainability. The entire focus was on environment protection.

Latin America

Corporations desirous of working in countries with socialist governments such as Uruguay, Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay and Venezuela, have their CSR programmes focussed on poverty reduction, protection of the natural environment, and providing water supply through extensive community engagement. On the other hand, in countries like Brazil and Peru, where the current establishments are pro-business, CSR programmes focus on ensuring a positive impact of business in the social and environment domains; though not necessarily through the community engagement route.

China

In recent years, an increasing concern of the Chinese Communist Party and the Chinese citizenry has been the adverse impact of the country’s rapid industrial expansion on the environment leading to pollution and degradation. Hence, for local and multinational companies in China, CSR initiatives are focussed on reduction in air, water and noise pollution, devising ways of alternative means of power production than those purely dependant on coal, and developing broad-based environmentally responsible corporate strategies.

USA

With its capitalist culture, health and higher education are predominantly in the commercial space. Hence, CSR is increasingly equated with creating shared value for multiple stakeholders. This is complemented by large individual and corporate foundations that contribute billions

of dollars annually towards philanthropy and charitable activities. In India, there are pressing issues across several social sectors, where companies can contribute through knowledge and resources, and make an impact through CSR projects. It may not be relevant to compare our approach with other countries, yet we can emulate successful CSR projects and dovetail them to suit our domestic requirements. Remember, we are four times the size of the US-population and less than one-third of its area. We have 12 times the complexities!

CSR implementation models

In my decade-long research, I have noticed three distinct CSR implementation models:

• Corporations establish foundations/trusts that give grants to NGOs for implementing projects in diverse areas. Their role is limited to funding, followed by impact evaluation through third-party agencies.

• Corporations partner with NGOs and jointly execute CSR projects. The company brings in funds and committed manpower through proactive social volunteering programmes. NGOs bring in field expertise.

• Corporations establish foundations and have dedicated full-time staff that accomplish the CSR mandate of the parent organisation.

In each of these there are unique challenges. However, there are a few approaches that can lead to win-win outcomes:

• Identify a core area that a company wants to contribute to and then delve deeper. This would help move the needle in that space over a longer term, rather than spread resources over a dozen causes. Dig two deep wells that provide water, rather than 20 pits with no depth and water!

• Develop a rigorous multi-layered selection process for NGO partners that resonate with the company’s vision and mission. This would lead to greater synergies and focused output in the long-term, rather than trying a new NGO every year.

• Build capacity within partner NGOs. Most social sector organisations have immense passion and commitment to purpose. However, they lack the implementation rigour of large corporations. Their existential focus remains on fund-raising and reporting. It would be mutually beneficial to invest in training them on simple management concepts. The CSR legislation has a provision of spending 10 per cent of the annual CSR funds on training employees and partner agencies. In a project on ‘Livelihood Creation in India’ that I led at the Harvard University South Asia Institute, this need for capacity building emerged as a major requirement of NGOs and social enterprises.

• Corporations tend to invest in fancy CSR projects which may have little to do with their core competence. It would do them immense good if their CSR projects resonate with their larger identity. For example, in my recent book Win-Win Corporations, I have elaborated how India’s largest chain of hotels invested substantial efforts and resources in livelihood training connected with the hospitality sector. These are win-win CSR strategies.

CSR in the next decade

As I’ve elaborated in my magnum opus on CSR – Soulful Corporations, CSR needs to transition from an activity undertaken due to external/legal pressure to a public relations strategy. From that stage it must graduate to a formal, internal business process of dealing with ethical, social and environmental concerns; and finally become an integral, core business activity which is the outcome of close interactions with the firm’s key stakeholders. I believe corporate India has already embarked on this multi-stage journey.

In the last four years, the Ministry of Corporate Affairs has issued many circulars permitting contributions to projects like Namami Gange and Swachh Bharat as CSR. Besides, the ministry has given a reasonably open definition that any activity falling within the ambit of the spirit of the CSR legislation will qualify as CSR provided it does not give any commercial returns to the company. However, CSR projects can give brand and goodwill-related returns in enormous measure. A prudent organisation can capitalise on this latent advantage. For example, a soap company can increase hygiene-related awareness in reducing preventive diseases, and further its brand as a personal care company.

Going forward, the momentum created by the initial compulsion could be self-sustaining. Over a period, the mandatory clause for CSR may become immaterial as companies would start experiencing benefits of their CSR activities for themselves and the target communities. If implemented in its letter and spirit, the multiplier effect of this collective contribution of corporate India through CSR could be far-reaching in the next decade, both for the country and its 1.3 billion citizens.

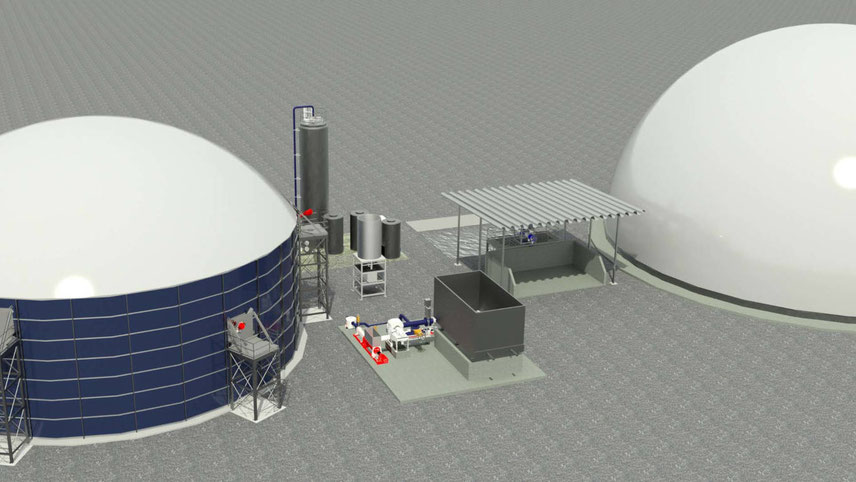

Biogas

BioEnergy will showcase its innovative biogas technology in India

Mobility

Ather aims to produce 20,000 units every month, soon

Green Hydrogen

German Development Agency, GIZ is working on a roadmap for a green hydrogen cluster in Kochi

Renewable Energy

AGEL set to play a big role in India’s carbon neutrality target