-

Doing good for society has generally also resulted in being good for business. Source: Peakpx

ndia has a remarkable opportunity with the advent of the CSR regulation to create a more ‘inclusive business’ mindset – a mindset that visionaries such as Jamsetji Tata dreamt of seeding in ‘its’ very DNA over a century ago, when they imagined that society would be a key stakeholder in business. We don’t think capitalism has failed our society. In fact, it has had an important role to play in lifting hundreds of millions out of poverty. Additionally, tens of millions who migrated overseas have benefitted from it, resulting in massive inflows of remittances back home that have again transformed lives. However, simultaneously, data suggests that inequality is also at multi-decade highs both in the west and in India. This is giving rise to anger, especially amongst many at the bottom of the pyramid who feel left out, or those who have seen conditions stagnate for long, while wealth has grown for those at the top, the glaring disparity being magnified in the age of social media. Hundreds of millions are now beginning to ask what constitutes a successful economic model and if there is an alternative? Simultaneously, a large number of millennials are thinking very differently about issues from our generation or the two before us. They are, rightly so, putting issues like the sustainability of the planet and responsible behaviour towards the environment much higher up on the list of issues they want to be addressed by corporations and governments. Against this backdrop, businesses can do a lot more to think about how to include some of the most marginalised sections of our society in their plans. If they do not, capitalism runs the risk of being attacked more and more viciously, to the point of breaking. This is where the CSR regulation actually steps in as a progressive one, and not as just another form of tax on corporations, as it was perceived by many when it was first introduced. Let us, however, take a step back and look at this mindset shift in doing business from only a ‘for-profit’ perspective, to a sustainable approach that embraces low-income or marginalised communities within its value chain, be it in the form of producers, vendors or consumers. Recent research done by Morgan Stanley indicated that from the consumer’s perspective, there is a marked shift in this direction. Over 63 per cent of global consumers already prefer to purchase products and services from purpose-driven brands and companies. So, building inclusive brands and companies is not going to be a burden in the future, but an asset. Starbucks is a good example of a global end-to-end sustainable value chain. One of the goals the company set was to ethically source its coffee and they have now managed to achieve that to a 99 per cent level. Further, Starbucks plans to completely eliminate the use of plastic in all its stores by next year. It is no surprise that consumers the world over resonate Starbucks’ approach. Unilever, the global FMCG major, is another example of a firm that is making strides in this regard. While in India, they have been doing some pioneering work, including in the area of water; globally they launched the Enhancing Livelihoods Fund (ELF). This fund, in partnership with Oxfam and the Ford Foundation, provides a mix of loans, guarantees and matching grants for Unilever suppliers to improve agricultural practices and empower women. Women-led households participating in the programme saw a 30 per cent yield increase and an overall 50 per cent increase in net income per crop. All these examples showcase global majors who are embracing inclusive business practices. Unilever’s Sustainable Living Plan, the vision and brainchild of Paul Polman, serves as a blueprint today and is used across the company to define the values and principles that guide its operations. It sets specific targets aligned with Sustainable Development Goals and reports on its progress to ensure accountability. In India, at the grassroots level, Amul has built its reputation for developing an effective rural development model to enable inclusive growth for many decades. Using a co-operative model, Amul teaches small and marginalised milk producers about scientific cattle-breeding techniques, provides, supplies and credits and invests in storage infrastructure. Its efforts have effectively created an entire industry and transformed the lives of thousands of farmers. Also, in the context of industry, microfinance is an example of a successful model, which provides credible alternative solutions to address the cost of credit access at the ‘bottom of the pyramid’ (BoP). In both these cases, it is well-proven that inclusive businesses need not be either unprofitable or limited in scale. India has been blessed with legendary figures such as Jamsetji Tata, Jamnalal Bajaj and Azim Premji, who have established and, or, managed big conglomerates. At the core of their philosophy is a combination of not only seeing great wealth creation through vibrant enterprise but also way before Corporate Social Responsibility was mandated by the government, they believed that business should do the right thing for society and exist meaningfully for the sake of it. This is the true essence of being inclusive. It needs to come from the heart even more than from any regulation.

-

We have met a pharma leader who built a factory with 20 per cent of its workforce with people with special needs. It never faced union problems when factories around it were struggling.

In all our travels, we have come across many amazing inclusive business initiatives, some going back many decades. We have met a pharma leader who built a factory with 20 per cent of its workforce with people with special needs. It never faced union problems when factories around it were struggling. We have met a visionary MNC leader, who returned to India and transformed his company by building his workforce by hiring large numbers of women on the shop floor. It not only changed his company’s performance but also had a big impact on the community.

A dynamic woman leader from South India has done similarly with parts of her business. What surprises us the most is that all these stories show that inclusiveness doesn’t come at a cost to the companies, but that doing good for society has generally also resulted in being good for business. It makes us wonder why these case studies have not been carefully documented or researched so that they could be scaled across corporate India. It makes us wonder if corporate India would have different outcomes as a whole on, say, productivity, if we have more gender inclusivity in the workforce or if we have more representation from people who are specially-abled and relevantly trained, or for that matter any other form of diversity.

Our final argument on inclusive business practices relates to capital. Data-based evidence suggests that not only consumers but also, investors are increasingly demanding integration of ESG into investment decision making through the Responsible Investment (RI) movement. At the beginning of 2018, $11.6 trillion of all professionally managed assets – one $1 of every $4 invested in the US – were under ESG investment strategies, a sharp increase from 2010, when the amount was close to just $3 trillion overall. Millennials are twice as likely to invest in companies or funds that target social or environmental outcomes. A recent paper titled Public Sentiment and the Price of Corporate Sustainability, by George Serafeim, professor, Harvard Business School, claims that an increase in a firm’s ESG performance has nearly two to three times the effect on a firm’s market valuation for a firm with positive, relative to a firm with negative public sentiment momentum.

In conclusion, we believe that being inclusive is something businesses should embrace as a core approach. Whether it is the environment or the communities we work with, if we can make the effort to be thoughtful about how to do two things – by first ensuring we do no harm on how we work; and, second, include to the best extent possible those left out in the process of moving forward with our mission – we will not only build great companies but also great and sustainable societies.

*This column has been co-authored with Priyanka Nagpal Dhingra, ATE, Chandra Foundation

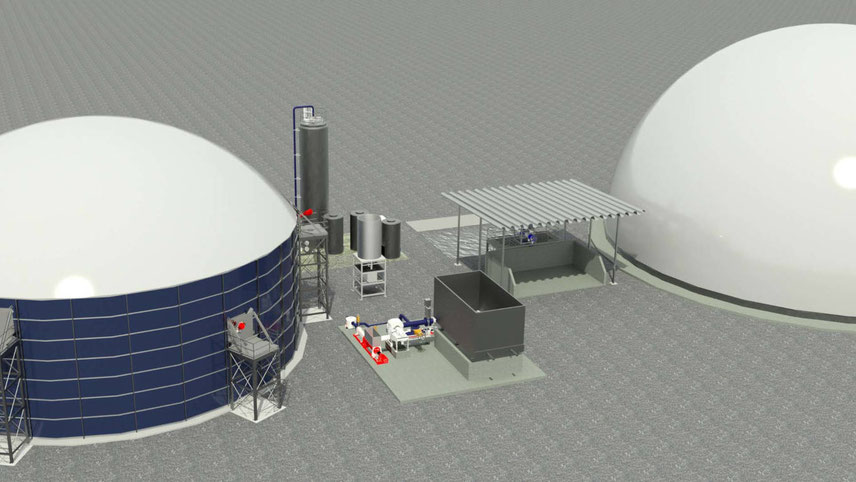

Biogas

BioEnergy will showcase its innovative biogas technology in India

Mobility

Ather aims to produce 20,000 units every month, soon

Green Hydrogen

German Development Agency, GIZ is working on a roadmap for a green hydrogen cluster in Kochi

Renewable Energy

AGEL set to play a big role in India’s carbon neutrality target