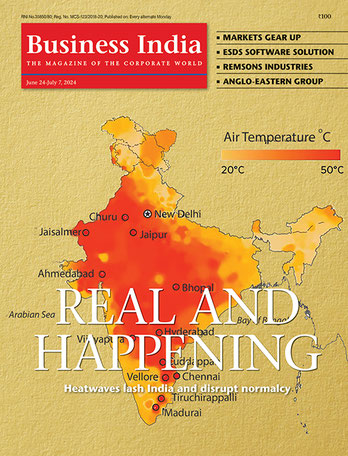

According to Bloomberg and International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) report on Financial Stability Indicators of Countries for 2018, India emerged as a country with the highest bad-loan ratios (10.8 per cent) among the top 10 world economies. The power sector remained a key contributor to this problem where the lenders in the country are staring at about $25 billion worth of thermal power assets classified as non-performing assets (NPAs). Total 34 thermal power plants with a capacity of about 40,000 MW are classified as stressed assets. With the RBI tightening norms around NPA classification and a requirement of mandatory restructuring of the debt within 180 days, it rattled companies in power sectors as well as lending communities. The Supreme Court (SC) as well as the government swung into action and the SC intervened in the matter staying the RBI’s directive on classification and treatment of bad loans. Likewise, the government also formed a High-Level Empowered Committee (HLEP) under the chairmanship of the Cabinet Secretary to come up with a plan to resolve issues around the stressed thermal power projects. The HLEP analysed the situation and pointed out the following key reasons for distress in thermal power segment: • Aggressive tariffs quoted by bidders in competitive bidding process • Regulatory and contractual disputes • Delayed payments by DISCOMs • Inability of promoters to infuse equity and service debt • Falling plant load factors (PLF) of thermal power plants (78.8 per cent in FY07 to 59.88 per cent in FY18) A similar set of observations were being recorded in the Forum of Regulators (FoR) report on Competitive Tariff vis-a-vis Cost plus Tariff – Critical Analysis published in 2017. While these issues are being tackled through various administrative initiatives, when India is adding up its renewable energy capacity at a rate unprecedented, the “thermal problem” seems far away from a reasonable resolution. The orange story: In 2015, India announced a very ambitious target of achieving 175 GW of renewable energy capacity by 2022. About 100 GW of it, expected to come from only solar energy. Further, as per the announcement made by India during the 17th meeting of the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) council meeting held at Abu Dhabi in September’19, the target has now been further scaled up to achieve 500 GW of renewable energy by 2030. In 2017-18, India achieved something for the first time. India added more capacity in renewables (11,788 MW) than in the thermal and hydro sectors combined (5,400 MW). Further, as on July 2019, according to the ministry of new and renewable energy, India has already reached 81.3 GW of renewable energy installations. Further, tariffs of solar energy in India have reduced significantly over the last 10 years. According to IRENA’s report titled Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2018, India has emerged as the lowest-cost producer of Solar energy leaving behind China, Germany, Italy and France. The costs for utility-scale solar projects in India have dropped fastest (~80 per cent) in India compared to any other country in the world between 2010 and 2018. While the journey of renewables in terms of capacity addition and fast falling price discovery of solar energy bids have been almost exemplary in India over the past nine years, there are visible similarities surfacing between the thermal story and the renewable story in India. • Aggressive tariffs: In May 2017, India discovered an all-time low tariff of 2.44/kWh ($ 0.034 as in Sep’19) in Rajasthan, Bhadla Solar Phase III solar park auction, where ACME Solar got awarded 200 MW of solar capacity. Many in the industry then also termed the new price discovered as “a race to extinction”. However, the race is still continuing, and all the subsequent capacity allocation auctions across India have seen tariff discovery in the range of Rs2.47/kWh ($ 0.035/kWh) to Rs2.91/kWh ($ 0.041/kWh). • Regulatory and contractual disputes: The fast-falling solar tariffs also created tariff pressure on other renewable generation technologies especially for wind, where the existing feed-in-tariffs in many states took a long uncertain pause. The declining tariffs in each subsequent solar auction caused insecurities among utilities having committed higher prices for their earlier solar procurements. Thus, the objective of “discovering best tariff” through nerve exhausting electronic reverse-auctions (e-RA) did not end with the completion of each auction. It rather extended further towards the results of the next auction and an auction after. States like Karnataka – which created one of the best solar policies in the country for open-access, backtracked from their commitment retrospectively. Likewise, Andhra Pradesh recently proposed to renegotiate legally binding power purchase agreements (PPAs) signed with the wind and solar developers in Andhra Pradesh. Both the matters are now pending for judicial decisions. • Delayed Payments by DISCOMs: When it comes to payments from public DISCOMs in India, renewables are no different than thermal. Payment delays beyond few years (not months) are a new norm. In select few states, in order to get payment from DISCOMs, the generator would be required to forgo late payment charges on their dues (along with interest) and further be ready to take a haircut on their net outstanding amount in order to get “priority” over other claimants. According to the Central Energy Agency’s (CEA) recent report on Payment Dues on re Generators, as on August 2019, the total dues from the DISCOMs to RE generators in India amounts to Rs11,458 crore ($1.605 billion) which also includes an amount of Rs1,722.5 crore ($241.3 million) from one generation company alone who initially reported the dues and withdrawn it later. Top five states (Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, Karnataka, and Madhya Pradesh) alone constitute about 86 per cent of net dues to renewable sector. According to PRAPTI portal maintained by the ministry of power (MoP), many states like Haryana, Rajasthan, Bihar, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka have been reported to take as long as 790 days and more to clear their dues.