-

India called the NDC ‘fair and ambitious’, though its contribution to climate change was ‘limited'

In its own words, India called the NDC ‘fair and ambitious’, though its contribution to climate change was ‘limited’. At the Paris negotiations, India surprisingly accepted the 1.5 degrees goal for climate policy given that it could potentially be used to close the gates on carbon emissions from late industrialising nations.

India also launched the International Solar Alliance (ISA) on the sidelines of COP 21 and is aggressively pushing for expansion of its renewable energy programme with a domestic goal of 175 GW of renewable energy by 2022. India also quickly ratified the Paris Agreement to help bring it into force.

Between Paris and New York, however, not much has moved in actual terms in areas that matter. As per the common but differentiated responsibilities agreed upon, developed countries were to provide adequate finance, technology and capacity building to facilitate the effective implementation of the climate change convention and the Paris Agreement. However, the reality is that the implementation of NDCs of developing countries has hit a roadblock in the face of an uncertain future in the provisioning of climate finance. India’s Economic Survey 2019, presented earlier this year, too had conceded that finding the financial resources to meet the NDCs under climate action would be a ‘daunting challenge’.

During the 2009 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), developed countries committed to ‘a goal of mobilising jointly $100 billion a year by 2020 to address the needs of developing countries’ and it was decided that a significant portion of such funding would flow through the Copenhagen Green Climate Fund (GCF). But, as on July this year, the total pledges to the GCF are a meagre $10.3 billion and only $0.39 billion has been disbursed so far. India has chided the western nations saying their call for stepping up climate actions will have to be matched with adequate provision of climate finance to developing countries. “Climate finance is a key pillar in enabling climate actions. Enhanced ambition and enhanced support should be on an equal footing,” says a top Indian official, involved in policy formulation in the past.

In its NDC, India has said it would need about $206 billion (at 2014-15 prices) between 2015 and 2030, to implement adaptation actions in key areas such as agriculture and fisheries. The total preliminary estimate for meeting India’s climate change actions between 2015 and 2030 is $2.5 trillion (at 2014-15 prices), says the latest calculation of the Union finance ministry. And, that is a tall order.

Trump’s spanner:

A major spanner in the works has come from the US under Donald Trump, which has walked out of the Paris climate agreement. Trump has blamed India and China for not doing enough on climate change, labelling them as regions with air that is impossible to breathe. Back home, the Trump administration is also moving to rescind a host of environmental rules, including those governing emissions of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, in a bid to boost the domestic economy. Last year, emission levels in the US had increased, while current US policies are expected to make future reductions less likely. According to a report by the Union of Concerned Scientists, the US is the world’s second-largest polluter after China, and contributes 15 per cent of global CO2 emissions. China emits 27 per cent, the EU 10 per cent and India 6 per cent.

The moves by Trump and the US to sit out the summit notwithstanding, UN deliberations have gone on. UN’s Guterres has suggested that he’s looking past the US’ federal government for progress – and directly to the Americans to fight climate change. Yes, a number of states, cities and companies in the US have stepped up their efforts. But those ‘sub-national’ efforts won’t put the US on track to meet the international commitments made under former President Barack Obama, which would have required his successor to implement and build on his rules. It will now be up to other countries, led by the likes of the UK (which has committed to reduce Britain’s net carbon emission levels down to zero by 2050) to strengthen their existing pledges under the Paris agreement.

One reason the Paris deal came through was that it was a subject close to Obama’s heart. In the run-up to Paris, Obama had used his personal charm to woo Modi and India, traditionally seen as a hold-out in a tough climate deal. Winning Modi also helped Obama get other countries like South Africa and Brazil on board. Before that Obama had broken the ice with China. Reportedly, the former US President pledged technology and finance to help India overcome the transition to a green economy. But Obama is no longer there. India could play a key role in finding a middle path here. But will the world listen to Modi?

As it is, the international community is beginning to raise questions about the role developing countries play in the fight against climate change. India is the third-largest producer in the world of climate change – inducing greenhouse gas emissions, after China and the US. Voices are already being heard that India’s commitments under the Paris Climate Treaty, including the reduction of the carbon intensity of its GDP by 33-35 per cent by 2030, and the generation of 40 per cent of its energy from renewable sources, may not exactly yield a decline in greenhouse gas production. Also, with the 8 per cent-plus growth rate that India aspires for to generate jobs for its youth, greenhouse gas production could actually increase in India.

-

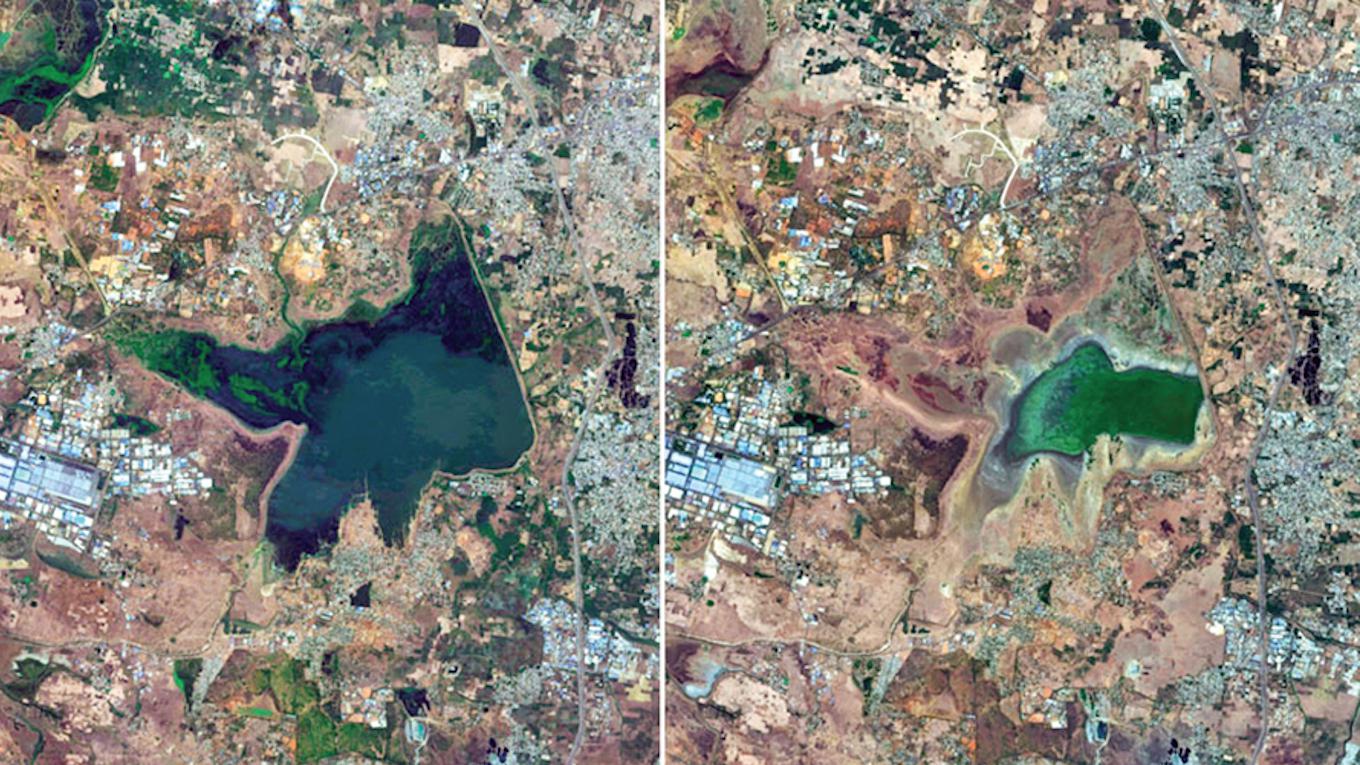

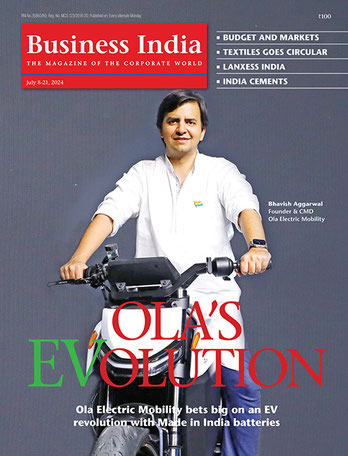

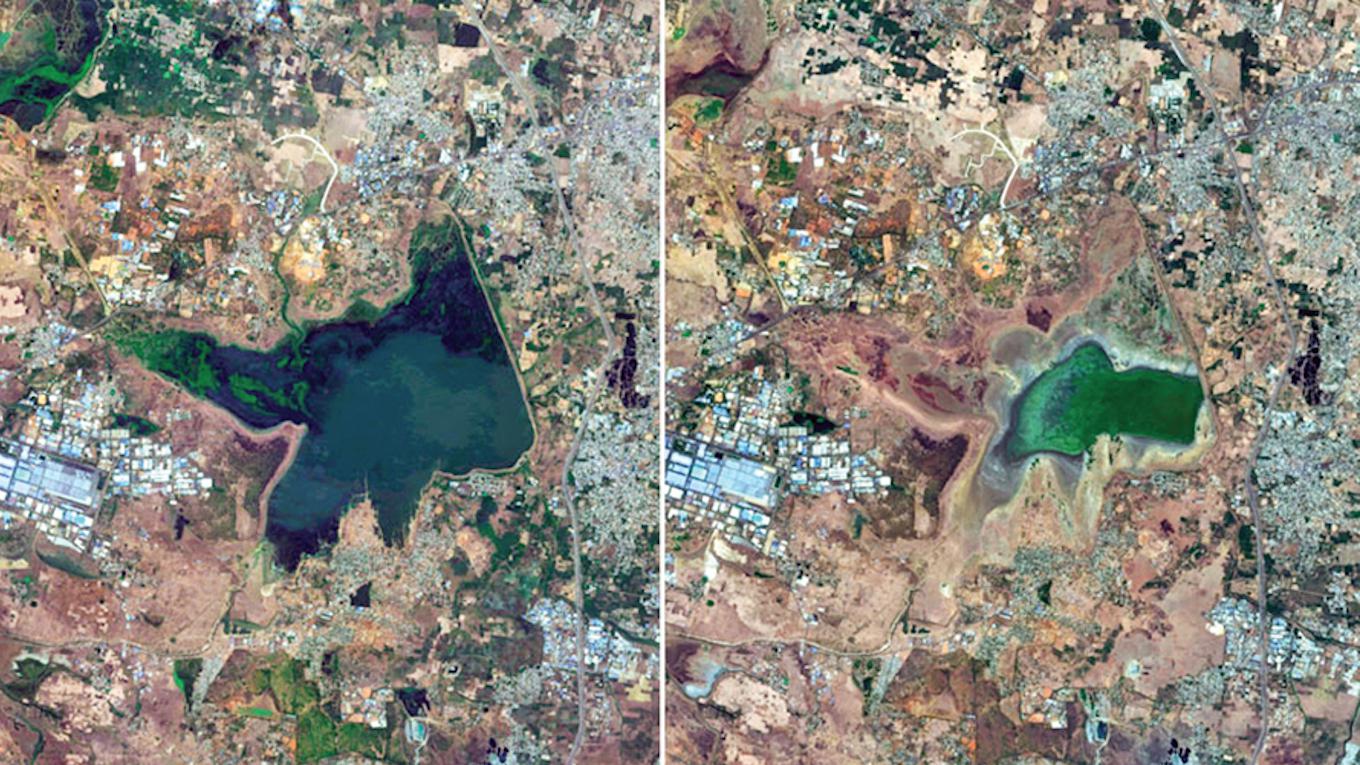

A file picture of a drying lake in Chennai

Involving industry:

With developed nations going slow on funding, the best bet for climate change mitigation lies in getting industry involved in the fight against climate change. In this connection, India will be leading the Industry Transition Coalition along with Sweden at the three-day summit in New York before the start of the annual high-level meeting of the General Assembly. The segment is to involve industries in fighting climate change and to cut down their emission of greenhouse gases. Several CEOs – from chemicals, cement, steel, aluminium, trucking, shipping, aviation sectors, et al – are expected to make commitments to net-zero emissions of greenhouse gases by 2050 during this segment of the summit.

Back home, India will need to take the corporate sector on board, asking it to demonstrate greater resource use efficiency, and invest in both greenhouse gas mitigation and climate adaptation. But how will India Inc. respond? “Awareness is certainly increasing, with events like the Chennai floods of 2015, which disrupted business continuity at some of India’s largest IT campuses, vividly bringing home the damage climate change can cause,” says Mukund Govind Rajan, chairman, ECube Investment Advisors, an ESG (environment, social and governance-focussed) fund. “Of course, the risks of business model disruption and stranded assets in major sectors of the economy like automobiles, power and construction are high. Corporate India needs to step up its investments on R&D and innovation, in order to adapt to the disruptive changes ahead, and to tap the opportunities presenting themselves in emerging spaces like electric mobility, renewable energy, waste management, and green buildings.” Here, a broader policy of incentives will help, like it was done for EVs in the last budget.

‘Huge success’:

India, on its part, maintains that it is doing its best to meet the promised adaptation and mitigation actions. Prakash Javadekar, Union minister for environment, forest & climate change, claims that India’s ambitious renewable energy programme “is a huge success and we have already reduced energy intensity by 22 per cent”. In his address to the Indian community at the UNESCO headquarters in Paris this August, Modi said India will achieve most of the COP 21 (2015 Paris Conference) climate change goals set for 2030 in the next one and half years.

There is some truth in these claims. India has become one of the top renewable producers globally with ambitious capacity expansion plans. The country has an installed renewable energy capacity of about 80 GW and is running the world’s largest renewable energy programme. Investments in the country’s renewable energy sector doubled over the last five years to about $20 billion in 2018, surpassing the capital expenditure in the thermal power sector.

Solar energy has emerged as a leading segment of our green energy capacity. Despite policy glitches, the segment is growing. Adarsh Das, CEO, SunSource Energy, expects the solar energy segment to witness further expansion this year because of pent-up demand from commercial and industrial segments. “The main driver is the need to reduce electricity bills,” he says. However, the intermittent nature of renewable generation is a limiting factor. India needs grid-scale battery storage for the green energy it generates. It is only now that the government has realised that the reducing cost of batteries will help in a faster roll-out.

Yet, everybody who is anybody in the government of India admits that finance still remains a critical issue in addressing climate change. The transition to clean energy, for instance, is fundamentally a construction project. The challenge is as much about finding the capital to pay for the construction as it is finding the technology to deliver the necessary emissions reductions. We have to finance clean-energy infrastructure the same way we would finance any other construction project. Coal plants have needed and received project finance for decades; the same is now true for solar, wind, efficiency, microgrid, battery storage, and so on.

-

When states set ambitious renewable energy portfolio targets, it gets headlines. But a target is just a target without an implementation mechanism. The implementation doesn’t happen without finance solutions

When states set ambitious renewable energy portfolio targets, it gets headlines. But a target is just a target without an implementation mechanism. The implementation doesn’t happen without finance solutions. Here, the role of green banks becomes relevant. These banks provide a mechanism for moving to the next frontier of viable clean-energy markets and investing in the kind of technology and opportunities that are right on the edge of being financeable by the private sector but which the private sector is not yet inclined to take on themselves.

How can India under Modi, who (along with France’s Francois Hollande) floated the idea of ISA and hosted its first general assembly in October last year in New Delhi, assert its credentials as a climate change warrior to be taken seriously? In the coming months, India will no doubt highlight its ambitious Swachch Bharat mission, its recent efforts towards eliminating single-use plastic, harnessing solar and wind energy and, creating more tree cover for protection of environment at various UN Climate forums to claim the leadership position. Over the last few years, India has been trying to rejig its energy mix in favour of green energy sources. At present, India has an installed power generation capacity of 357,875 MW, of which about 22 per cent (say, 80,000 MW) is generated through clean energy projects such as solar and wind. With the addition of large hydro-projects to clean energy segment, India is poised to have 225 GW of renewable energy by 2022.

New initiative:

In its second term, the Modi government is showing significant seriousness in developing an environment-focused approach as a possible Indian normative pitch. By setting up an integrated ministry dedicated to tackling the country’s water crisis and elevating a farmer leader of the party who is cognizant of wide-spread rural water distress, Gajendra Singh Sekhawat, to head the ministry, and setting itself an ambitious project (about six times the scale of bringing electricity to every part of the country) of delivering tapped water to every household by 2024, the Modi government has indicated that it is serious about tackling climate change and its related problems at home. Similar to other successes like building toilets and providing electricity, this project has been described to be in ‘mission mode’ – a phrase used for projects receiving the highest importance and attention. If India succeeds in this project, it could yet lead the world in water conservation.

The announcement of an income tax rebate for customers of electronic vehicles in the first budget of the second term of the Modi government is the other indication of India trying to lead the way in adopting measures against climate change with an aim to convert most vehicles to electric-powered by 2030 and with an already achieved target of producing the world’s cheapest solar power. Under Modi’s watch, the latest assessments suggest that the country might exceed its own targets of replacing fossil fuel use with clean energy by 2030. Under current assessments, renewable energy might provide half of India’s energy needs by 2030 – up from the 40 per cent target set by Modi.

Speaking at the Eighth Asian Ministerial Energy Roundtable at Abu Dhabi on 10 September, where India was the co-host, along with the UAE, Dharmendra Pradhan, Union minister for petroleum, said, “The Energy Vision of India, as enunciated by Prime Minister Modi in 2016, is based on four pillars – energy access, energy efficiency, energy sustainability and energy security. As part of our integrated approach towards energy planning during the last five years, energy justice will be a key objective in itself. In this context, we are working towards the early realisation of the UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 7.”

Cooling action plan:

Green energy generation may be one thing. Critics say that India will have to get its act together on a host of other issues before it aspires for climate leadership. For instance, India became one of the first countries in the world to launch a comprehensive Cooling Action Plan in March 2019, which has a long-term vision to address the cooling requirement across sectors such as residential and commercial buildings, cold-chain, refrigeration, transport and industries. However, the India Cooling Action Plan (ICAP), which lists out actions that can help reduce the cooling demand, that will also help in reducing both direct and indirect emissions has been dismissed by some as ‘grossly inadequate’ and defined it as limited in scope.

-

"Lack of planning can completely upset the energy budget of the country"

Anumita Roychowdhury

The Centre for Science & Environment (CSE), for one, asked for immediate revision of the ICAP document to address the serious gaps, which it said if not rectified now can lock in ‘irreversible’ energy guzzling. “If we are planning to provide ‘sustainable cooling’ and ‘thermal comfort for all’, we cannot ignore the need of thermal comfort for 90 per cent of the country’s population, and also the requirements of a range of other services including agricultural cold chains, provision of safe vaccines, and many other services that require cooling to function,” says Anumita Roychowdhury, executive director, research & advocacy, CSE. “This lack of planning can completely upset the energy budget of the country. At the same time, the ICAP has not indicated the benchmark for thermal comfort that needs to guide energy efficiency measures for all users of active as well as passive cooling,” she adds.

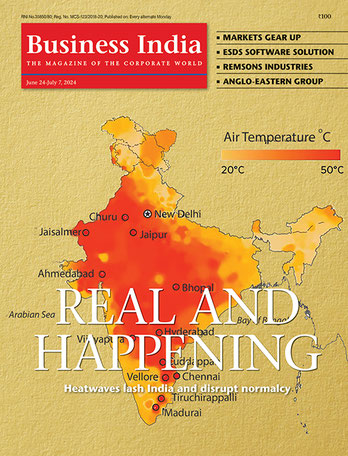

According to the CSE, while the ICAP aims to provide sustainable cooling and thermal comfort for all, its actual intent is ‘myopically’ focussed on only the market for personal air-conditioners, ignoring the fact that demand for cooling is driven by people and not by the sale of air conditioners. The CSE said ICAP must capture equity issue, ensure thermal comfort for all without over-dependence on active cooling. The green body said the ICAP must take note of the fact that about 60 per cent of current space cooling energy consumption is by top 10 per cent of the population. Over 96 per cent of transport cooling energy consumption is due to personal cars (13.5 per cent of the population) and this small minority skews electricity demand and locks in enormous carbon energy guzzling. “In Delhi, 25-30 per cent of annual energy consumption is because of thermal stress,” says CSE. “In peak summer, when energy demand soars, it is as much as 50 per cent of energy consumption.”

“When temperature drops, energy consumption in the city drops dramatically – from 6,346 MW to 3,323 MW (10 degrees Celsius drop leads to 48 per cent demand drop in energy, irrespective of the time of day), which points to the importance of cooling and heating in energy management,” it added.

Green buildings:

Environmental experts have also pointed out that India needs thermal comfort defined to guide interventions for energy efficiency in buildings. For this, national building codes should be amended to ensure all buildings are designed in a way that indoor conditions do not get hotter than the national goal for the majority of hours in the year, using passive design. There is also a need for more robust standards, labelling and testing methodology for ACs. This is a growing problem as, in 2017-18, about seven million cooling appliances were sold, and the number is likely to rise to 15 million in the next five-six years.

In response to this, the Bureau of Energy Efficiency (BEE) has recently announced that it is planning to introduce ‘energy conservation building code’ for residential buildings to help reduce domestic consumption. The BEE wants to tweak the existing energy conservation building code for commercial complexes like malls, institutions and office buildings to suit residential complexes. BEE has been working with household equipment manufacturers including AC makers for bringing down domestic and commercial power consumption. It hopes to achieve power savings of 40 GW by 2030 with the help of stricter conservation norms for ACs.

But critics point out these moves address only one side of the coin, the non-industrial side. The industrial and agricultural sectors still need better law frames and codes. Food and grains require cold storage as do the livestock market for storage, transport and exports. Hence, a comprehensive study is needed to give an actual assessment of cooling and thermal needs in India, which will bring a much better and well-adjusted picture.

Lack of data, planning:

India’s efforts at climate change mitigation were initially hamstrung by a host of factors, the major one being lack of data and planning. As such a complete region-wise picture of the impact of climate change in India was missing. It was just six months ago that a committee headed by N.H. Ravindanath, professor, Centre for Sustainable Technologies, Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru, was set up to prepare a national study. The committee is racing against time to finish the study.

Till recently, many states had their climate change action plan just on paper, though more than 25 states had submitted their plans for the Prime Minister’s National Climate Change Action Plan way back in 2013. Besides, in most states, state action plans on climate change (SAPCCs) have functioned as stand-alone documents, with limited recognition of the activities of other line departments which, if integrated, can bring forth collective climate action. Moreover, the scope of SAPCCs is largely restricted to state jurisdiction, without a clear vision at further de-centralised governance systems. Districts and cities are still largely neglected areas for climate action in the SAPCCs.

“To tackle this problem (climate change), there is a need to build a network of research institutions throughout India – some in Delhi, some in Assam, some in Gujarat and so on. This networking should be done under a national programme and there is a need to focus on this issue like a mission. We still do not have that kind of a mission approach,” says N.H. Ravindranath, IISC. “The government needs to have a plan. Once that is done they can assess how much money is required. Then they can identify the institutions that will be a part of this network.”

-

Will there be any takers for India’s logic?

Money, money, money:

The big question, however, is: where will India get all the money from for achieving these lofty goals? By an official estimate, India would need about $206 billion (at 2014-15 prices) between 2015 and 2030 to implement new technologies and practices in cultivation, improve crop production, increase forest cover, watershed development programmes, flood management and make cities climate-resilient in key areas such as agriculture, forestry, fisheries infrastructure, water resources, and ecosystems, according to initial estimates as given in the NDCs. Additional investments will be needed for greater resilience and better disaster management. The preliminary total estimate for meeting India’s climate change actions between now and 2030 is a huge $2.5 trillion (at 2014-15 prices).

India’s climate finance provisioning from its own sources has been tardy. In its latest budget, the Modi government allocated just Rs2,954.72 crore for the ministry for environment, forests & climate change, the nodal ministry dealing with climate change, as well as planning and overseeing the implementation of the country’s environmental and forest policies and programmes. Its focus areas include the conservation of flora and fauna, the prevention and control of pollution, afforestation and river conservation, while legislative measures like the National Forest Policy and the National Environment Policy guide its work. Budgetary allocations for the ministry include funding to a host of bodies with the Climate Change Action Plan being just one of them.

Individual allotments that have gone to the National Adaptation Fund for Climate Change (Rs100 crore) and National Mission for a Green India (Rs240 crore) are paltry. The National Adaptation Fund was set up in 2015-16 with an aim to support activities that could mitigate the adverse impacts of climate change. The National Mission for a Green India aims to increase the country’s green cover in terms of both extent and quality and to also improve ecosystem services such as hydrological services and forest-based livelihoods. Even a government report, titled ‘Performance of the National Action Plan on Climate Change’, admits that allocations made in the past have been ‘grossly insufficient’, as compared to committed liabilities.

Hence, in the run-up to the New York summit, India has again raised the pitch for finance and technology support to developing nations to achieve the Paris Agreement goals of keeping a global average temperature rise this century well below 2 degrees Celsius. So far, India has blamed the developed countries for not keeping up to their commitment of providing $100 billion and technology transfer collectively to developing countries like India for dealing with climate change. It has held that the developed world is responsible for most of the climate change situation today. Over 70 per cent of the greenhouse gases emission is due to the developed countries, while India’s contribution is just 3 per cent. This is because of overconsumption by the people in the developed world, goes India’s argument.

Any takers?

But will there be any takers for India’s logic? “In Chile, when we meet in the next COP (Conference of the Parties), we will be taking a stance that every country needs to follow their own commitments to reduce national emissions and advanced countries need to provide finance and technology support, that is most important to developing world,” says Javadekar. New Delhi hopes to draw support, among others, from the basic group of nations – Brazil, South Africa, India and China – which want developed countries to undertake ambitious actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and meet their financial commitments. But who will loosen the purse-strings, when the world is in the grip of an economic slowdown?

A few years ago, when the Paris Agreement was adopted, India made four commitments, including reducing greenhouse gas emission intensity of its GDP, basing 40 per cent of its power capacity would be based on non-fossil fuel sources, creating an additional ‘carbon sink’ of 2.5-3 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent through additional forest and tree cover, and enhancing investments in development programmes in sectors vulnerable to climate change, particularly agriculture, water resources, Himalayan region, coastal regions, health and disaster management. By any reckoning, this will be a long haul. Meanwhile, the after-effects of climate change will become more and more visible to us as they did recently – extreme precipitation in cities like Mumbai, which caused serious flooding; rain deficit in New Delhi, which made September warmer than ever before; and the delayed withdrawal of the southwest monsoon, which we are witnessing now.